Who's story?

Back in 1689 Locke wrote An Essay Concerning Human Understanding which, in part, explored the notion as to what identity means when human nature is so changeable. the cells of our bodies regenerate over time, such that the body I have today is not cell-for-cell the same as the body I inhabited twenty years ago (for one thing, there's rather more of it). Not only is my flesh different, but my mind has changed. I have filled my head with a thousand books and hundreds of stories and have been emotionally changed by the people I've met in those two decades - some for the better, and some much for the worse. Whilst some things have remained constant, such as devotion to the Lonely God of Gallifrey, other things have been lost and some things gained.

Whilst I feel as if I am the same person, it is difficult to argue what it is that is the same. Christians, Muslims, and Hindus might suggest that it is the soul that acts as the eternal constant around which body and mind revolve. I am a believer in the existence of a unifying divine spark but for me this is a rather nebulous belief and I would be hard pressed to give a coherent account as to what I think that spark actually is.

Locke uses the allegory of a prince whose mind is paced into the body of a cobbler (whose soul has departed). For Locke, the prince will always believe himself to be the prince even when he looks in the mirror and sees the face of the cobbler. Of course, back in 1689 the understanding of neurology was minimal, and the debates around the impact of genetics on personality where barely begun - if a mind is transferred into a body with a totally different DNA, with a subtly different brain structure and neurochemical range, would that mind be altered to fit the new biological parameters? Until it actually happens outside the pages of fiction, it remains unknowable.

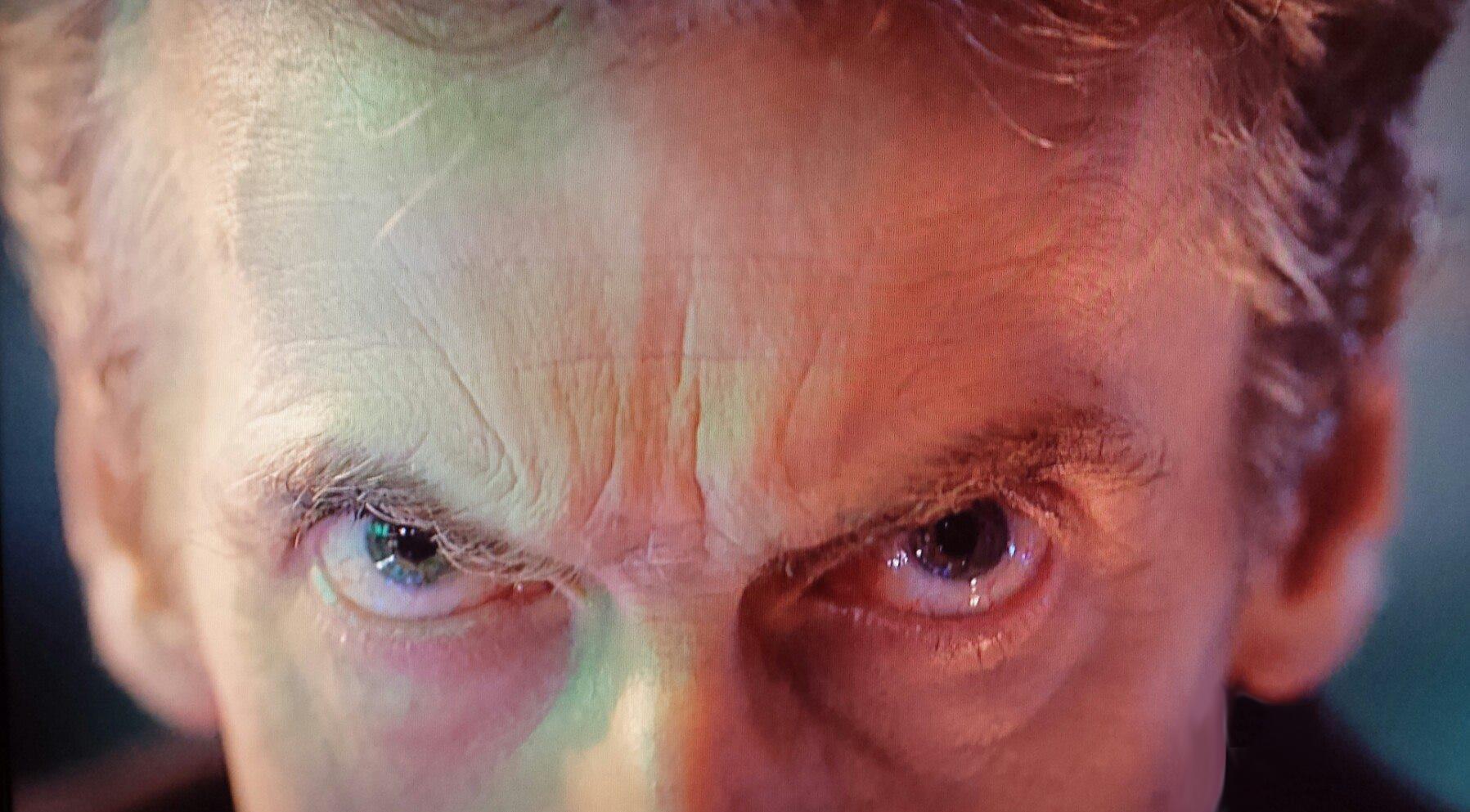

With the Doctor his regenerations are into bodies so different that one has to assume that his DNA changes (not that the show has ever addressed the mechanics of what actually happens) and so perhaps this explains why his personality is also variable from body to body. Is it just the memories that echo from body to body, from mind to mind? We are arguably the sum of our memories, which in small part makes Alzheimer's such a terrifying condition - robbing people of their very sense of self, of continuity between changes of mind and body, of memory.

Is soul essentially memory? Like most people I have lost memories - I know that I had birthday parties as a child, but can remember next to nothing about them. Maybe under hypnosis some memories would be retrievable, so the threat of losing bits of ones soul may be illusory. If it is memory, then parts of it may be recoverable in much the same way as shamans suggest. Though if it is simply memory, then so many people's souls must be horrifically maimed by the unspeakable things which haunt them. Perhaps it is better to hope that the soul is more than the sum of memories, or that the Waters of Lethe really do grant the nepenthean gift of forgetfulness.

Within a communitarian ethic, we are each the product of a collaborative effort between ourselves and others. This is not in the rather grey way that some sociologists seem to think, but a dynamic process in which we actively work with others to create ourselves and help shape them in turn. Early Anglo-Saxon storytellers were called scops, from which we get the modern English word shape. The tellers of stories shape the world in which they live - or perhaps are simply the vehicles by which stories transmit themselves. The author Terry Pratchett said, "People think that stories are shaped by people. In fact it's the other way round". He's correct, and perhaps souls are not so much a set of memories as a narrative.

Stories are collaborative works, shaped between teller and audience - and within oral cultures (which have been and remain the dominant form of culture) are not the property of any one teller, but flow from one word-weaver to the next. We may tell our own stories, but we collaborate on them with our audiences - the people who listen to our stories... and sometimes the people who refuse to listen as well. Stories are composed of silences as well as words.

The story of the Doctor passes from regeneration to regeneration, as our narratives pass from our child selves to our spotty teenage selves to our middle-aged spread selves to our frail elderly selves. Sometimes our stories can be stolen from us, which we mostly see happening at a collective level where a disenfranchised group can face having its story deliberately eradicated or forcibly rewritten to make it more appetising to whoever is in power. Achille Mbembe speaks of destructible bodies within his theory of necropower - socially powerful groups writing off unwanted sectors of society and leaving them to die (or actively slaughtering them). Stories can outlive a peoples, like the myths of the Sumerians, but sometimes the stories predecease the people and they become invisible and forgettable even as their hearts still beat.

When Michael Grade killed off the Doctor in 1989, his stories continued on in the hearts of the people to whom they sang - in novels, fan films, comics, and the like - till eventually he returned to full life on screen in 2005. Likewise the Gods and major narratives of the past can appear to die off, but continue in the hearts of a few until such time as they regenerate. Perhaps it is not just human souls that pass from body to body, but the souls of deities and other beings - narrative beings, like us, but on an epic scale, whose stories refuse to ever completely die.

Comments

Post a Comment